About Dangerzone

Original by Micah Lee, with additions from Dangerzone contributors

Have you ever heard the computer security advice, “Don’t open attachments”? This is solid advice, but unfortunately for journalists, activists, and many other people, it’s impossible to follow. Imagine if you were a journalist and got an email from someone claiming to work for the Trump Organization with “Donald Trump tax returns.pdf” attached. Are you really going to reply saying, “Sorry, I don’t open attachments” and leave it at that?

The truth is, as a journalist, it’s your job to open documents from strangers, whether you get them in an email, a Signal or WhatsApp message, or through SecureDrop. Journalists also must open and read documents downloaded from all manner of websites, from leaked or hacked email dumps, or from any number of other potentially untrustworthy sources.

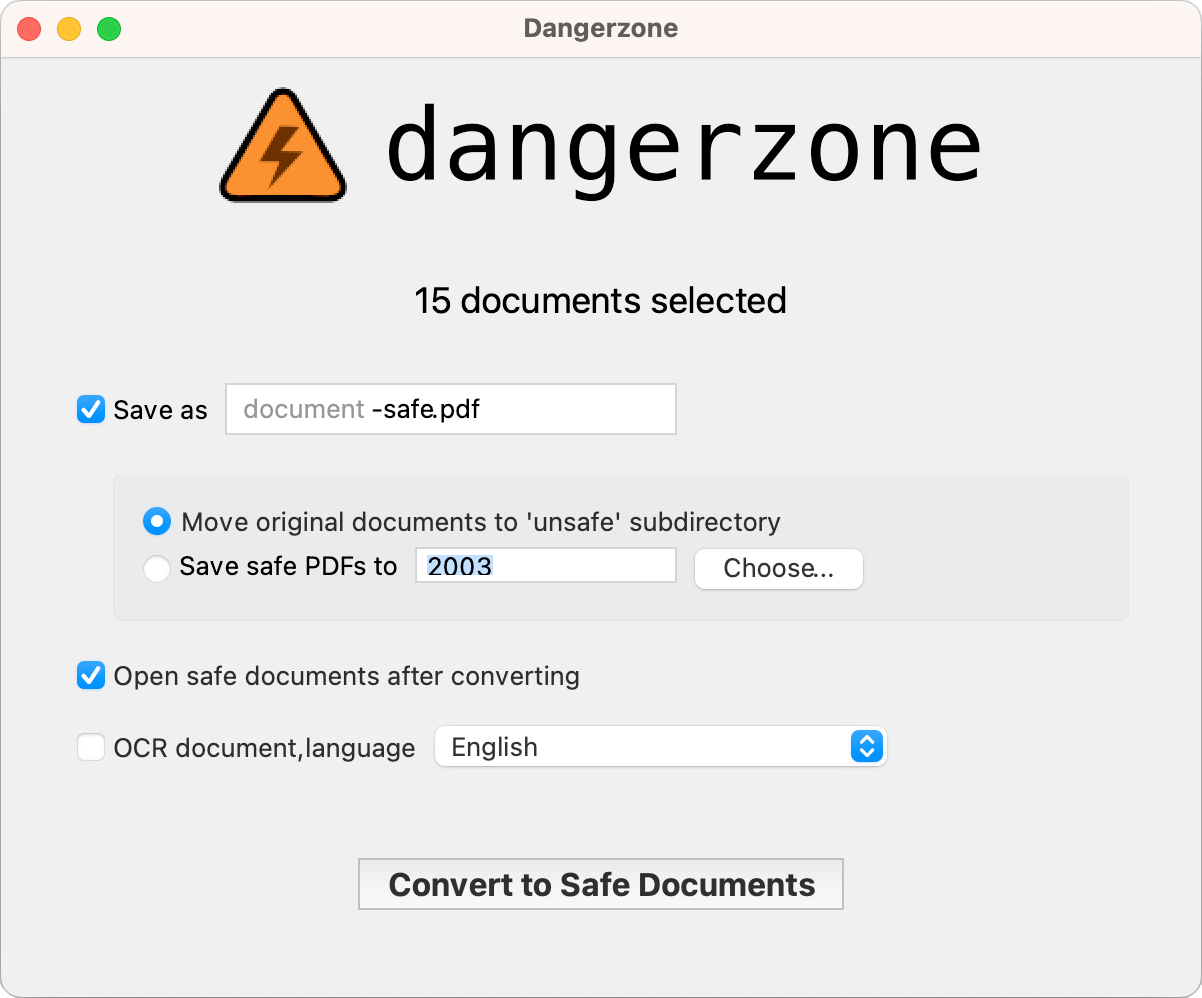

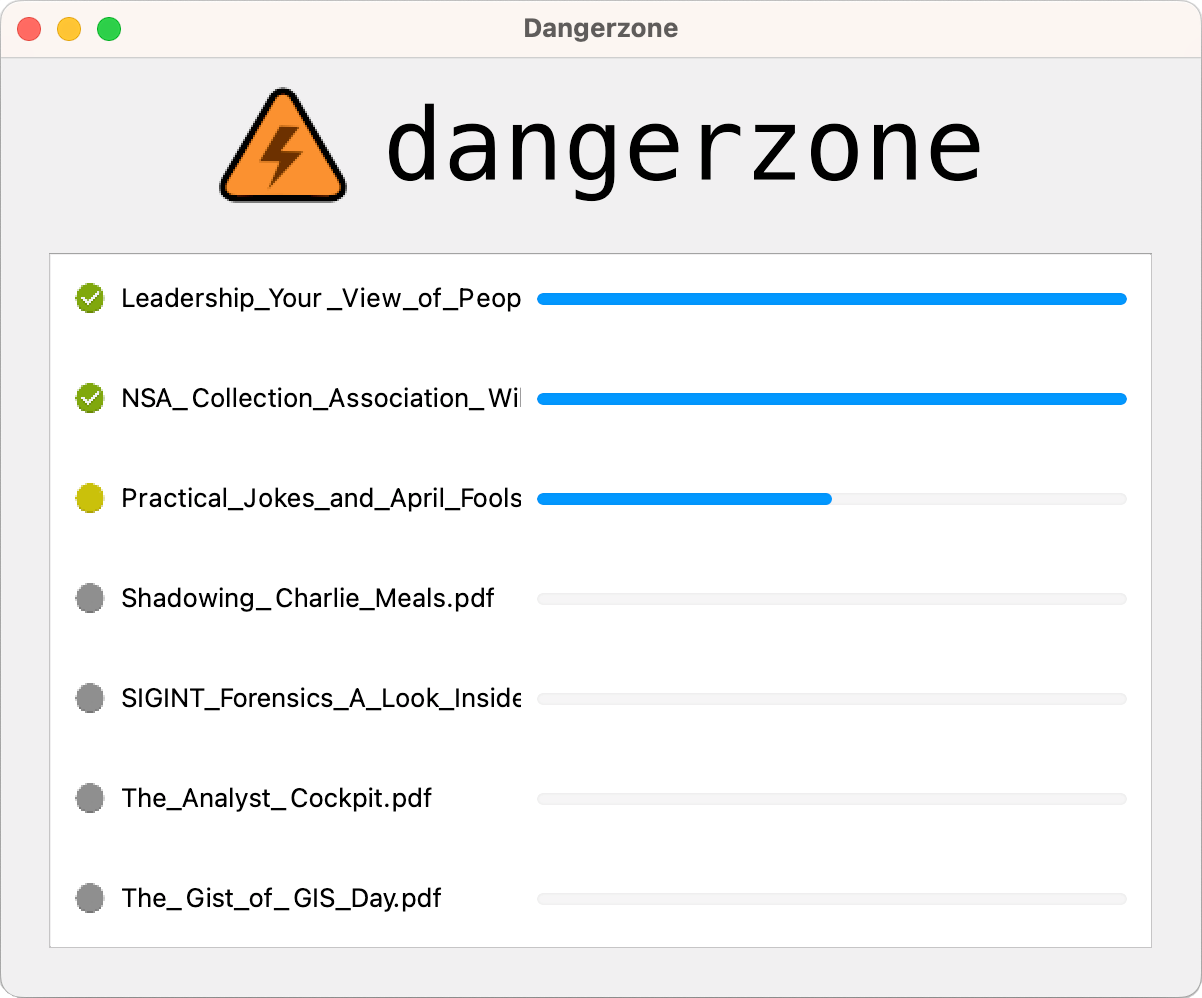

Dangerzone aims to solve this problem. You can install Dangerzone on your Mac, Windows, or Linux computer, and then use it to open a variety of types of documents: PDFs, Microsoft Office or LibreOffice documents, or images. Even if the original document is dangerous and would normally hack your computer, Dangerzone will convert it into a safe PDF that you can open and read.

You can think of it like printing a document and then rescanning it to remove anything sketchy, except all done in software.

Download Dangerzone for Windows, macOS or Linux to get started.

How can a document be dangerous?

PDFs and office documents are incredibly complex. They can be made to automatically load an image from a remote server when the document is open, tracking when a document is opened and from what IP address. They can contain JavaScript or macros that, depending on how your software is configured, could automatically execute code when opened, potentially taking over your computer. And finally, like all software, the programs you use to open documents – Preview, Adobe Reader, Microsoft Word, LibreOffice, etc. – have bugs, and these bugs can sometimes be exploited to take over your computer. (You can reduce your risk of getting hacked by always installing your updates, which fix the bugs that software vendors are aware of.)

For example, if an attacker knows about a security bug in Microsoft Word, they can carefully craft a Word document that, when opened using a vulnerable version of Word, will hack your computer. All they have to do is trick you into opening it, perhaps by sending you a convincing enough phishing email.

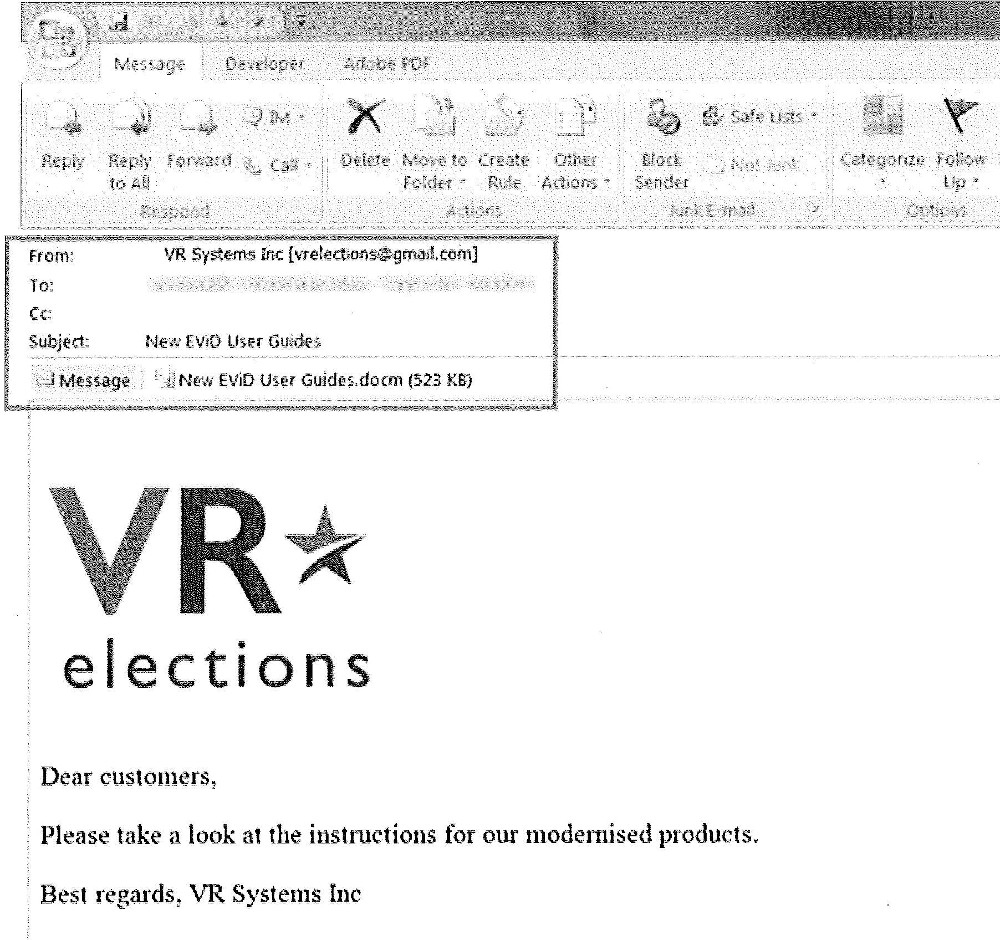

This is exactly what Russian military intelligence did during the 2016 US election. First, they hacked a US election vendor known as VR Systems and got their client list. Then they send 122 emails to VR Systems’ clients (election workers in swing states) from the email address [email protected], with the attachment "New EViD User Guides.docm".

Screenshot of spearphishing email provided to The Intercept from a North Carolina public records request

If any of the election workers who got this email opened the attachment using a vulnerable version of Word in Windows, the malware would have created a backdoor into their computer for the Russian hackers. (We don’t know if anyone opened the document or not, but they might have.)

If you got this email today and opened New EViD User Guides.docm using Dangerzone, it will convert it into a safe PDF (New EViD User Guides-safe.pdf), and you can safely open this document in a PDF viewer, without risking getting hacked.

Inspired by Qubes TrustedPDF

I got the idea for Dangerzone from Qubes, an operating system that runs everything in virtual machines. In Qubes, you can right-click on a PDF and choose “Convert to TrustedPDF”. I gave a talk called Qubes OS: The Operating System That Can Protect You Even If You Get Hacked in 2018 at the Circle of HOPE hacker conference in New York. I talk about how TrustedPDF works for about 2 minutes starting at 9:20.

Dangerzone was inspired by TrustedPDF but it works in non-Qubes operating systems, which is important, because most of the journalists I know use Macs and probably won’t be jumping to Qubes for some time.

It uses gVisor sandboxes running in Linux containers to open dangerous documents, instead of virtual machines. And it also adds some features that TrustedPDF doesn’t have: it works with any office documents, not just PDFs; it uses optical character recognition (OCR) to make the safe PDF have a searchable text layer; and it compresses the final safe PDF.

How does Dangerzone work?

Dangerzone uses Linux containers, which are isolated application environments that share the Linux kernel with their host. On Windows and macOS, it uses Podman under the hood, which spins containers in a dedicated virtual machine. Since Dangerzone 0.10.0, all this complexity is hidden from the user.

When Dangerzone starts the container that will sanitize the suspicious document, it will first start a gVisor sandbox inside that container, then run the potentially-dangerous document processing workload inside the sandbox. This ensures that the process dealing with the document is isolated from the Linux kernel. The sandbox and its parent container are also both configured to disable networking and to not mount anything from the host filesystem. So if a malicious document manages to execute arbitrary code, this code doesn’t have access to the host kernel, doesn't have access to your data, and can't use the internet, so there’s not much it could do.

Here’s how it works. First, the sandbox:

- Reads the original document from standard input

- Uses LibreOffice or PyMuPDF to convert original document to a PDF

- Uses PyMuPDF to split PDF into individual pages, and to convert those into RGB pixel data

- Writes the number of pages and the RGB pixel data to its standard output

Then that sandbox quits. The host reads the RGB pixel data from the container's standard output and:

- If OCR is enabled, uses PyMuPDF to convert RGB pixel data into a compressed, searchable PDF

- Otherwise uses PyMuPDF to convert RGB pixel data into a compressed, flat PDF

- Stores the safe PDF in the specified directory with the

-safe.pdfsuffix, and archives the original one

The user can then open the newly created safe PDF.

Here are types of documents that Dangerzone can convert into safe PDFs:

- PDF (.pdf)

- Microsoft Word (.docx, .doc)

- Microsoft Excel (.xlsx, .xls)

- Microsoft PowerPoint (.pptx, .ppt)

- ODF Text (.odt)

- ODF Spreadsheet (.ods)

- ODF Presentation (.odp)

- ODF Graphics (.odg)

- EPUB (.epub)

- Jpeg (.jpg, .jpeg)

- GIF (.gif)

- PNG (.png)

- SVG (.svg)

- TIFF (.tif, .tiff)

- Other image formats (.bmp, .pnm, .pbm, ppm)

It’s still possible to get hacked with Dangerzone

Like all software, it’s possible that Dangerzone (and more importantly, the software that it relies on like LibreOffice and Podman) has security bugs. Malicious documents are designed to target a specific piece of software – for example, Adobe Reader on Mac. It’s possible that someone could craft a malicious document that specifically targets Dangerzone itself. An attacker would need to chain these exploits together to succeed at hacking Dangerzone:

- An exploit for either LibreOffice or PyMuPDF

- A sandbox escape exploit in the gVisor kernel

- A container escape exploit in the Linux kernel that isn't protected by gVisor's syscall filters

- In Mac and Windows, a VM escape exploit for Podman

For example, let's say that you open a malicious .docx file that specifically targets Dangerzone. What Dangerzone would do first is to start a Linux container, then start a gVisor sandbox within it, and finally begin the conversion process into a PDF using LibreOffice. If the malicious document wants to escape to the host, it first needs to exploit a vulnerability in LibreOffice to achieve code execution. Once it has control of LibreOffice, it needs to exploit a vulnerability in the gVisor kernel to escape the sandbox. Assuming it finds one, it then needs to find a different vulnerability in the Linux kernel to escape the container, and from there attempt to take over the computer.

If you keep Dangerzone updated regularly, such attacks will be much more expensive for attackers.

Another way a malicious document may harm your system, even with Dangerzone, is if it is crafted to attack the document previewing capabilities of the operating system itself (e.g. the part that generates file thumbnails or document previews in a side-panel of the file manager). Due to the high level of integration of these features in the operating system, disabling them completely may be challenging. For this reason, keeping your system always up to date is the most practical solution to minimize this risk.

While we are doing our best to inform journalists about these risks and keep them as safe as possible, we believe it's important for third parties to independently assess our assumptions. For this reason, Dangerzone underwent its first security audit on December 2023 by Include Security with support from the Open Technology Fund. The audit was generally favorable, as it didn't identify any high-risk findings (it identified 3 low-risk and 7 informational findings).

What others have written about Dangerzone

- When security matters: working with Qubes OS at the Guardian, by The Guardian on April 4, 2024

- GIJN Toolbox: Cutting-Edge — and Free — Online Investigative Tools You Can Try Right Now, by GIJN on March 13, 2024

Dangerzone is open source

This tool is still in early development, so there may be bugs. If you find any, please check the issues on GitHub and open one if your issue doesn’t exist. Please start discussions and make pull requests if you’d like to get involved.

You can find the code for the Mac, Windows, Linux graphical app and the document conversion process here: https://github.com/freedomofpress/dangerzone

Dangerzone is released under the AGPLv3 license. It was developed by Micah Lee at First Look Media and is now a project of Freedom of the Press Foundation.